Security pros don’t need screaming headlines to put them on alert about a dangerous new piece of malware.

“New” and “present” are usually enough to do it, though “stealthy” and “nasty” will open their eyes a little wider.

“In the world of malware threats, only a few rare examples can truly be considered groundbreaking and almost peerless,” reads the opening sentence of Symantec’s white paper on Regin.” What we have seen in Regin is just such a class of malware.”

The phrase “class of malware,” in this case referred to the sophistication level of the software, not its origin or intent – which appears to be long-term corporate and political espionage committed by a major national intelligence agency.

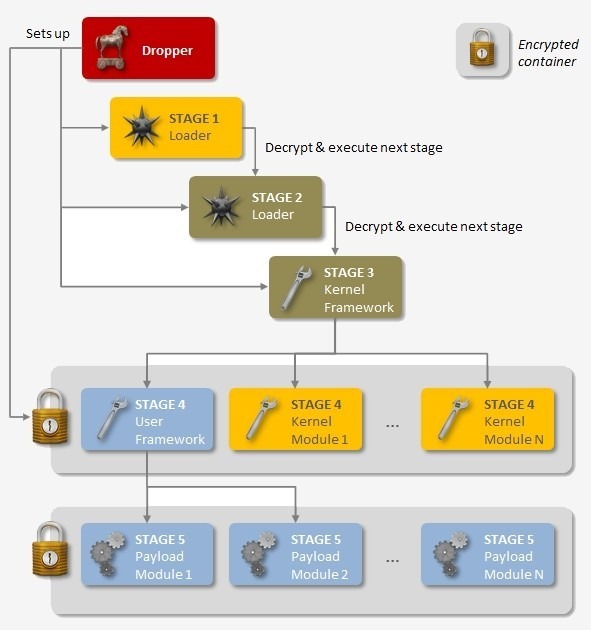

Regin’s architecture is so complex and programming so sophisticated, Symantec researchers concluded, that it is most likely to have been developed by a state-sponsored intelligence agency like the NSA or CIA, rather than hackers or malware writers motivated by profit or commercial developers such as the Italian company Hacking Team that sell software designed for espionage to governments and law enforcement agencies worldwide.

Far more important than the polish or architecture on the newly discovered malware, however, is the consistency in targets and approach, which are similar to those of previously identified apps designed for international espionage and sabotage including Stuxnet, Duqu, Flamer, Red October and Weevil – all of which have been blamed on the U.S. National Security Agency or CIA, though only Stuxnet has been confirmed to have been developed by the U.S

“Its capabilities and the level of resources behind Regin indicate that it is one of the main cyber-espionage tools used by a nation state,” according to Symantec’s report, which did not suggest which state might have been responsible.

But who?

There have been no Regin attacks on either China or the U.S.

Russia was the target of 28 percent of attacks; Saudi Arabia (a U.S. ally with which relations are often tense) was the target of 24 percent of Regin attacks. Mexico and Ireland each netted 9 percent of attacks. India, Afghanistan, Iran, Belgium, Austria and Pakistan got 5 percent apiece, according to Symantec’s breakdown.

Nearly half of attacks were aimed at “private individuals and small businesses;” telecom and Internet backbone companies were the target of 28 percent of attacks, though they likely served only as a way for Regin to get to businesses it had actually targeted, O’Murchu told Re/Code.

“It looks like it comes from a Western organization,” Symantec researcher Sian John told the BBC. “It’s the level of skill and expertise, the length of time over which it was developed.”

The approach of Regin resembles Stuxnet less than it does Duqu, a sly, shape-shifting Trojan designed to “steal everything” according to a 2012 Kaspersky Lab analysis.

One consistent feature that led to John’s conclusion is the hide-and-stay-resident design of Regin, which is consistent for an organization wanting to monitor an infected organization for years rather than penetrate, grab a few files and move on to the next target – a pattern that is more consistent with the approach of the known cyberspy organizations of China’s military than with that of the U.S.

China’s cyberespionage style is much more smash-and-grab, according to security firm FireEye, Inc., whose 2013 report “APT 1: Exposing One of China’s Cyber Espionage Units” detailed a persistent pattern of attack using malware and spear phishing that allowed one unit of the People’s Liberation Army to steal “hundreds of terabytes of data from at least 141 organizations.”

It’s unlikely the incredibly obvious attacks of PLA Unit 61398 – five of whose officers were the subject of an unprecedented espionage indictment of active-duty members of a foreign military by the U.S. Department of Justice earlier this year – are the only cyberspies in China, or that its lack of subtlety is characteristic of all Chinese cyberespionage efforts.

Though its efforts at cyberespionage are less well known than those of either the U.S. or China, Russia has a healthy cyber-spy and malware-producing operation of its own.

Malware known as APT28 has been traced to “a government sponsor based in Moscow,” according to an October, 2014 report from FireEye. The report described APT28 as “collecting intelligence that would be useful to a government,” meaning data on foreign militaries, governments and security organizations, especially those of former Soviet Bloc countries and NATO installations.

The important thing about Regin – at least to corporate infosecurity people – is that the risk that it will be used to attack any U.S.-based corporation is low.

The important thing to everyone else is that Regin is another bit of evidence of an ongoing cyberwar among the big three superpowers and a dozen or so secondary players, all of whom want to demonstrate they’ve got game online, none of which want a demonstration so extravagant it will expose all their cyber powers or prompt a physical attack in response to a digital one.

It also pushes the envelope of what we knew was possible from a bit of malware whose primary goal is to remain undetected so it can spy for a long time.

The ways it accomplishes that are easily clever enough to inspire admiration of its technical accomplishments – but only from those who don’t have to worry about having to detect, fight or eradicate malware that qualifies for the same league and Regin and Stuxnet and Duqu, but plays for another team.

via computerworld.com