Eric Evenchick knows what it’s like to be at the mercy of modes of transport. That might be why the former Tesla intern is so keen to hack his way to gaining greater control over the vehicles he travels in. When we speak over encrypted call app RedPhone, he’s stuck in Hong Kong airport waiting for a delayed flight to Singapore, where he’ll announce the open sourcing of the CANard tool during the BlackHat Asia conference.

His code will make it cheaper and easier than ever before for tinkerers to get to the innards of their connected cars to determine if there are any useful tweaks they can make, or any worrisome security vulnerabilities that more malicious hackers could exploit. Evenchick is hopeful CANard, based on the widely-used and much-loved Python language, will have a greater impact on the car industry in general. It should allow security researchers of all ilks to easily probe cars for weaknesses, which, Evenchick hopes, will get them to take vehicle hacking more seriously.

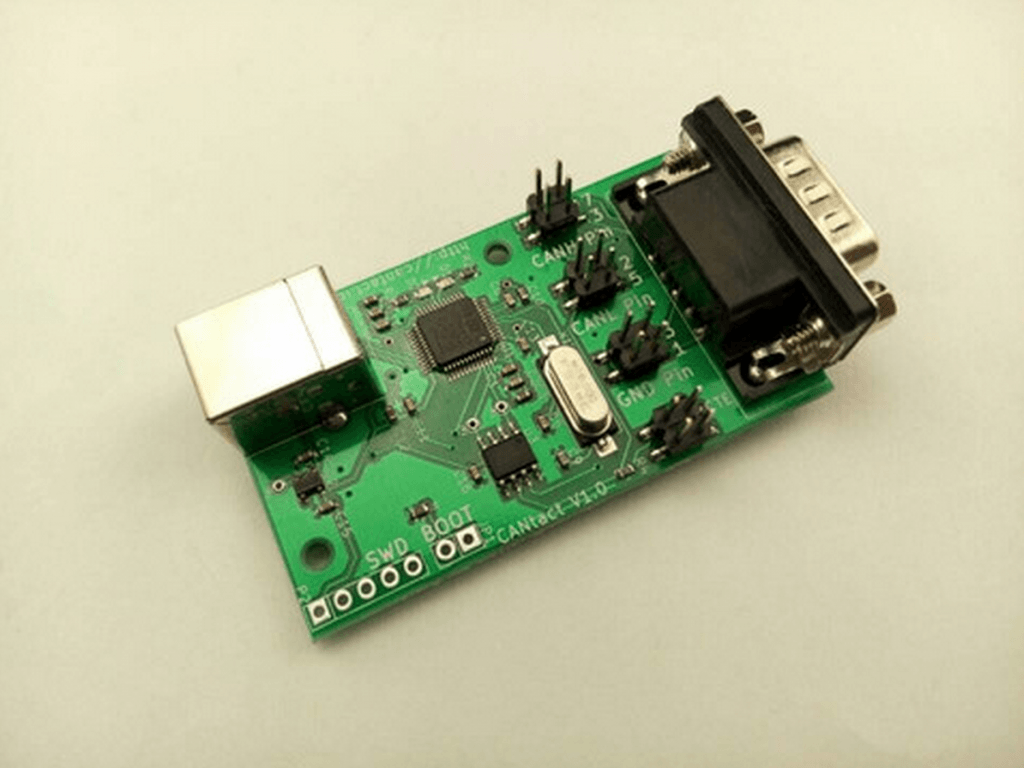

His own tinkering with the code has turned CANard into a more powerful tool in recent weeks. In particular, it now has the ability to carry out proper diagnostics over the Controller Area Network (CAN), the network-on-wheels found in almost all modern automobiles to send data around the vehicle, he tells FORBES. This means anyone who knows or learns Python (it’s a good language for newcomers to coding) can start to probe what functions can be accessed using their computer, whether they run an Apple AAPL +0.71% Mac, Microsoft MSFT -0.6% Windows or Linux PC. They’ll also need to buy some associated hardware to connect laptops to the diagnostics, or OBD2, port, which Evenchick has also produced. He’ll be shipping CANtact, a CAN to USB interface for the low, low price of $59.95 (USB and OBD2 cable not included). There will only be 100 available in the first batch, but the hardware is open source too, meaning it’s easily replicable and even cheaper for those with the right skills.

In recent months, breaches of car security have been repeatedly carried out by the security research community. In January, Corey Thuen revealed a startling lack of security in an OBD2 dongle from Progressive Insurance. Later in the year, DARPA-backed hackers took control of a car remotely using a laptop.

Previously, car hacking was the domain of those who had access to more expensive, bespoke hardware and knew the protocols used by cars. But it has been increasingly opened up to the masses in recent years. Researchers Chris Valasek and Charlie Miller open sourced their own car cracking tools back in 2013, which also contained Python scripts for vulnerability testing, followed by a guide to hacking vehicles without actually having access to an automobile. But they didn’t include the hardware component as Evenchick has done and he believes his full toolset is more accessible that what has come before.

“I want to make this easy. Python developers can get the code in one line … and start working with it. It’s also built as a library rather than just a collection of scripts. The plan is to build more functionality out around it, and contribute that back into an open source tool,” he says over email after our call.

Craig Smith, founder of the OpenGarages car security body and CEO at security research firm Theia Labs, believes Evenchick’s open source tools are great for lowering the barrier of entry for researchers and anyone interested in understanding how their car works. As vehicles can have upwards of 100 million lines of code running on them, it’s makes it essential as many security researchers as possible can validate these systems, he adds.

But there is still one “missing piece of the puzzle”: what to do with researchers’ findings. “Very few auto manufacturers have published processes detailing how a researcher should contact them about their findings. Without these policies researchers do not know how to contact the manufacturers in a way that will be productive in addressing the issue. This can lead to researchers being sued and/or getting cease and desist letters.”

Evenchick has been working on car technology for almost half a decade, during which time he interned at Tesla for four months in 2012, building some of the software functionality in the famous electric car. Though he isn’t permitted to go into detail on his time there, he says the company has one of the more responsible approaches to car security, with its bug bounty offering funds for vulnerability disclosures and a full information security programme.

Other car makers aren’t as forward-thinking, but a handful of new groups, in particular I Am The Cavalry, are working hard with industry and in Washington DC to enforce better practices across vehicle manufacturers. With pressure mounting on them to act, car companies might feel the need to act before a catastrophe strikes.