CANCUN, Mexico — In 2009, one or more prestigious researchers received a CD by mail that contained pictures and other materials from a recent scientific conference they attended in Houston. The scientists didn’t know it then, but the disc also delivered a malicious payload developed by a highly advanced hacking operation that had been active since at least 2001. The CD, it seems, was tampered with on its way through the mail.

It wasn’t the first time the operators—dubbed the “Equation Group” by researchers from Moscow-based Kaspersky Lab—had secretly intercepted a package in transit, booby-trapped its contents, and sent it to its intended destination. In 2002 or 2003, Equation Group members did something similar with an Oracle database installation CD in order to infect a different target with malware from the group’s extensive library. (Kaspersky settled on the name Equation Group because of members’ strong affinity for encryption algorithms, advanced obfuscation methods, and sophisticated techniques.)

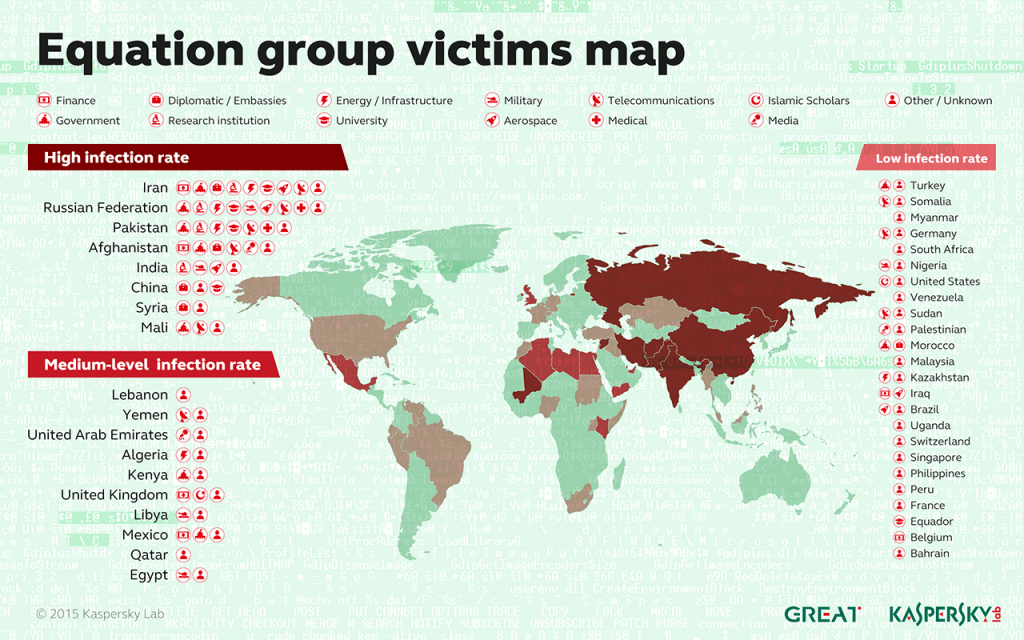

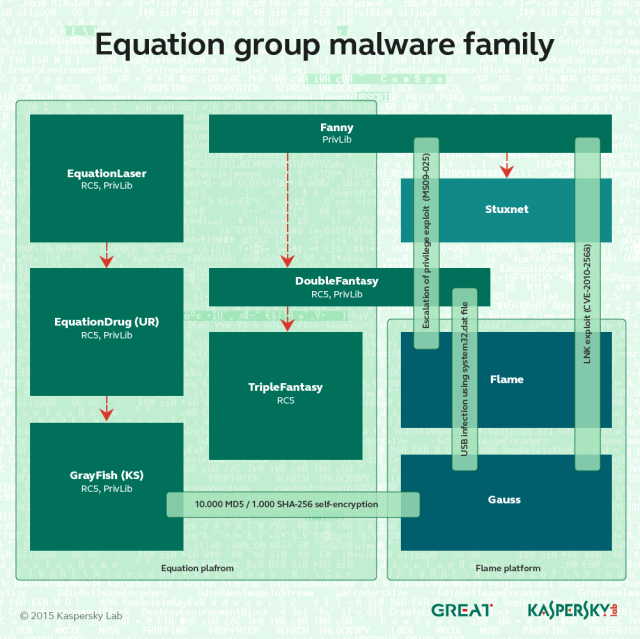

Kaspersky researchers have documented 500 infections by Equation Group in at least 42 countries, with Iran, Russia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Syria, and Mali topping the list. Because of a self-destruct mechanism built into the malware, the researchers suspect that this is just a tiny percentage of the total; the actual number of victims likely reaches into the tens of thousands.

A long list of almost superhuman technical feats illustrate Equation Group’s extraordinary skill, painstaking work, and unlimited resources. They include:

- The use of virtual file systems, a feature also found in the highly sophisticated Regin malware. Recently published documents provided by Ed Snowden indicate that the NSA used Regin to infect the partly state-owned Belgian firm Belgacom.

- The stashing of malicious files in multiple branches of an infected computer’s registry. By encrypting all malicious files and storing them in multiple branches of a computer’s Windows registry, the infection was impossible to detect using antivirus software.

- Redirects that sent iPhone users to unique exploit Web pages. In addition, infected machines reporting to Equation Group command servers identified themselves as Macs, an indication that the group successfully compromised both iOS and OS X devices.

- The use of more than 300 Internet domains and 100 servers to host a sprawling command and control infrastructure.

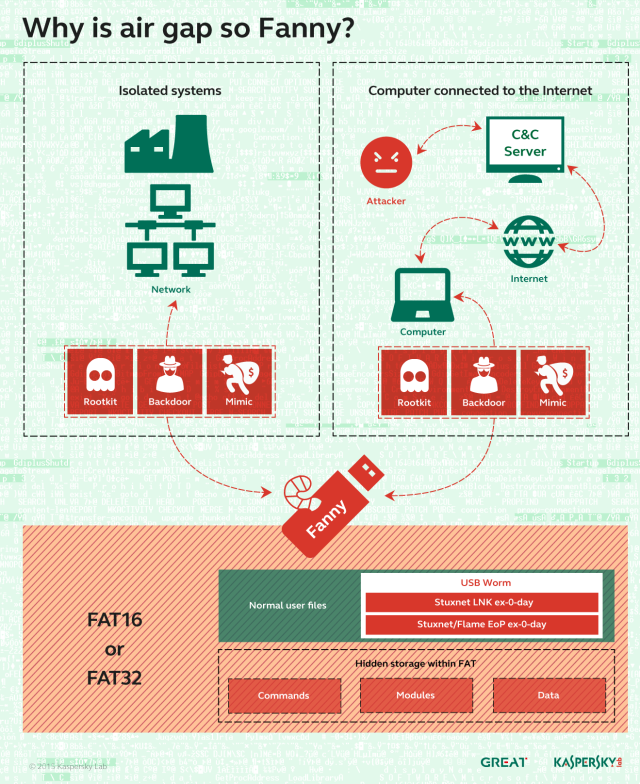

- USB stick-based reconnaissance malware to map air-gapped networks, which are so sensitive that they aren’t connected to the Internet. Both Stuxnet and the related Flame malware platform also had the ability to bridge airgaps.

- An unusual if not truly novel way of bypassing code-signing restrictions in modern versions of Windows, which require that all third-party software interfacing with the operating system kernel be digitally signed by a recognized certificate authority. To circumvent this restriction, Equation Group malware exploited a known vulnerability in an already signed driver for CloneCD to achieve kernel-level code execution.

Taken together, the accomplishments led Kaspersky researchers to conclude that Equation Group is probably the most sophisticated computer attack group in the world, with technical skill and resources that rival the groups that developed Stuxnet and the Flame espionage malware.

“It seems to me Equation Group are the ones with the coolest toys,” Costin Raiu, director of Kaspersky Lab’s global research and analysis team, told Ars. “Every now and then they share them with the Stuxnet group and the Flame group, but they are originally available only to the Equation Group people. Equation Group are definitely the masters, and they are giving the others, maybe, bread crumbs. From time to time they are giving them some goodies to integrate into Stuxnet and Flame.”

In an exhaustive report published Monday at the Kaspersky Security Analyst Summit here, researchers stopped short of saying Equation Group was the handiwork of the NSA—but they provided detailed evidence that strongly implicates the US spy agency.

First is the group’s known aptitude for conducting interdictions, such as installing covert implant firmware in a Cisco Systems router as it moved through the mail.

Second, a highly advanced keylogger in the Equation Group library refers to itself as “Grok” in its source code. The reference seems eerily similar to a line published last March in anIntercept article headlined “How the NSA Plans to Infect ‘Millions’ of Computers with Malware.” The article, which was based on Snowden-leaked documents, discussed an NSA-developed keylogger called Grok.

Third, other Equation Group source code makes reference to “STRAITACID” and “STRAITSHOOTER.” The code words bear a striking resemblance to “STRAITBIZARRE,” one of the most advanced malware platforms used by the NSA’s Tailored Access Operations unit. Besides sharing the unconventional spelling “strait,” Snowden-leaked documents note that STRAITBIZARRE could be turned into a disposable “shooter.” In addition, the codename FOXACID belonged to the same NSA malware framework as the Grok keylogger.

Apart from these shared code words, the Equation Group in 2008 used four zero-day vulnerabilities—including two that were later incorporated into Stuxnet.

The similarities don’t stop there. Equation Group malware dubbed GrayFish encrypted its payload with a 1,000-iteration hash of the target machine’s unique NTFS object ID. The technique makes it impossible for researchers to access the final payload without possessing the raw disk image for each individual infected machine. The technique closely resembles one used to conceal a potentially potent warhead in Gauss, a piece of highly advanced malware that shared strong technical similarities with both Stuxnet and Flame. (Stuxnet, according to The New York Times, was a joint operation between the NSA and Israel, while Flame, according to The Washington Post, was devised by the NSA, the CIA, and the Israeli military.)

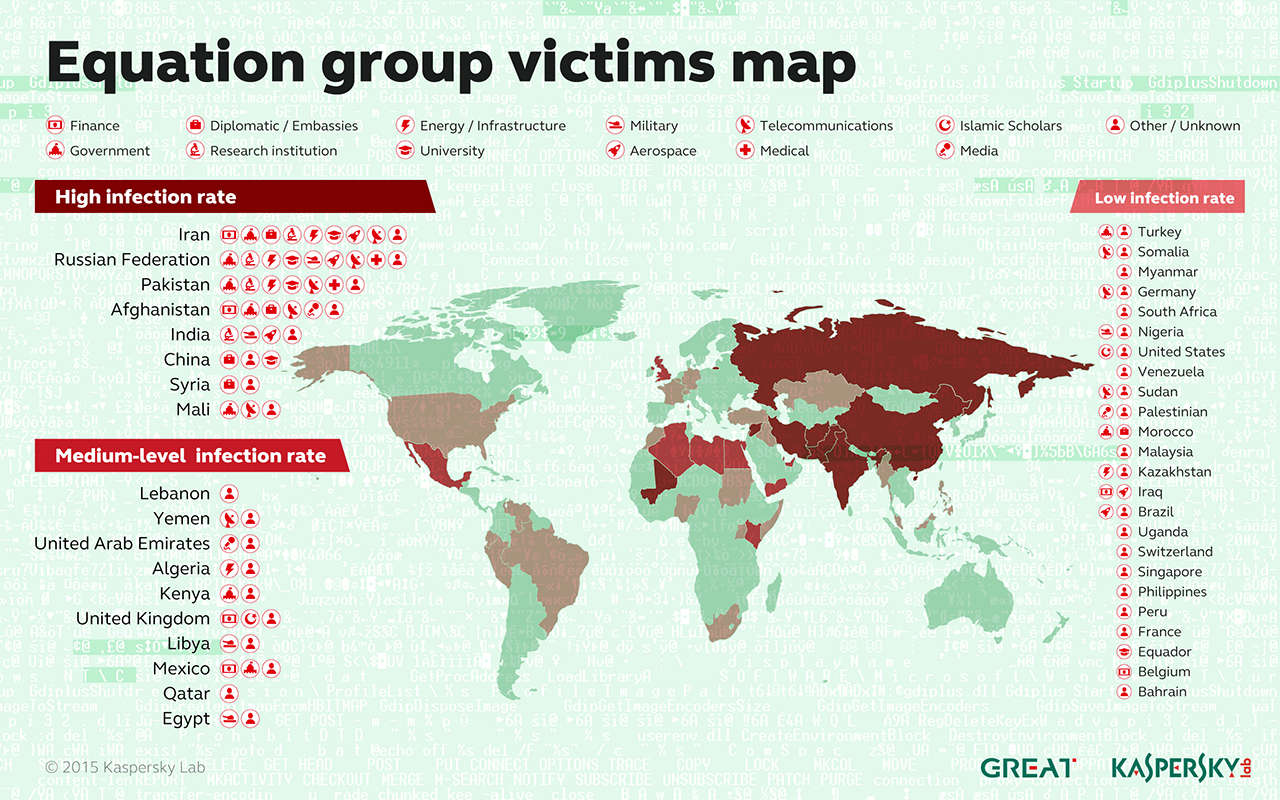

Beyond the technical similarities to the Stuxnet and Flame developers, Equation Group boasted the type of extraordinary engineering skill people have come to expect from a spy organization sponsored by the world’s wealthiest nation. One of the Equation Group’s malware platforms, for instance, rewrote the hard-drive firmware of infected computers—a never-before-seen engineering marvel that worked on 12 drive categories from manufacturers including Western Digital, Maxtor, Samsung, IBM, Micron, Toshiba, and Seagate.

The malicious firmware created a secret storage vault that survived military-grade disk wiping and reformatting, making sensitive data stolen from victims available even after reformatting the drive and reinstalling the operating system. The firmware also provided programming interfaces that other code in Equation Group’s sprawling malware library could access. Once a hard drive was compromised, the infection was impossible to detect or remove.

While it’s simple for end users to re-flash their hard drives using executable files provided by manufacturers, it’s just about impossible for an outsider to reverse engineer a hard drive, read the existing firmware, and create malicious versions.

“This is an incredibly complicated thing that was achieved by these guys, and they didn’t do it for one kind of hard drive brand,” Raiu said. “It’s very dangerous and bad because once a hard drive gets infected with this malicious payload it’s impossible for anyone, especially an antivirus [provider], to scan inside that hard drive firmware. It’s simply not possible to do that.”

Equation Group’s work

One of the most intriguing elements of Equation Group is its suspected use of interdiction to infect targets. Besides speaking to the group’s organization and advanced capabilities, such interceptions demonstrate the lengths to which the group will go to infect people of interest. The CD from the 2009 Houston conference—which Kaspersky declined to identify, except to say it was related to science—tried to use the autorun.inf mechanism in Windows to install malware dubbed DoubleFantasy. Kaspersky knows that conference organizers did send attendees a disc, and the company knows the identity of at least one conference participant who received a maliciously modified one, but company researchers provided few other details and don’t know precisely how the malicious content wound up on the disc.

“It would be very easy to trace the attack back to the organizers and point them out, and this could in turn result in some very serious diplomatic incidents,” Raiu said. “Our best guess is that the organizers didn’t act in a malicious way against the participants, but [that] some of the CD-ROMs on their way to the participants were intercepted and replaced with the malicious variants.”Even less is known about a CD for installing Oracle 8i-8.1.7 for Windows sent six or seven years earlier, except that it installed an early Equation Group malware program known as EquationLaser. The conference and Oracle CDs are the only Equation Group interdictions that Kaspersky researchers have discovered. Given how little is known about the interdictions, they weren’t likely to have been used often.

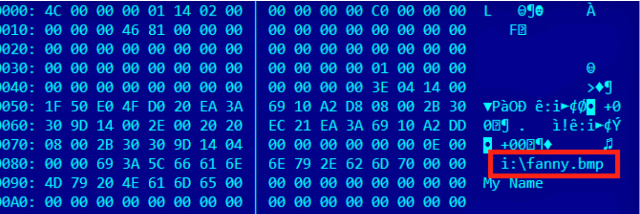

A separate method of infection relied on a worm introduced in 2008 that Kaspersky has dubbed Fanny, after a text string that appears in one of the zero-day exploits used by the worm to self-replicate. The then-unknown vulnerability resided in functions that process so-called .LNK files Windows uses to display icons when a USB stick is connected to a PC. By embedding malicious code inside the .LNK files, a booby-trapped stick could automatically infect the connected computer even when its autorun feature was turned off. The self-replication and lack of any dependence on a network connection made the vulnerability ideal for infecting air-gapped machines. (The .LNK vulnerability is classified as CVE-2010-2568.)

Some two years after first playing its role in Fanny, the .LNK exploit was added to a version of Stuxnet so that the worm could automatically spread through highly sensitive computers in Iran. Fanny also relied on an elevation-of-privilege vulnerability that was a zero day at the time the worm was introduced. In 2009, the exploit also made its way into Stuxnet, but by then, Microsoft had patched the underlying bug with the release of MS09-025.

A far more common infection vector was Web-based attacks that exploited vulnerabilities in Oracle’s Java software framework or in Internet Explorer. The exploits were hosted on a variety of websites related to everything from reviews of technology products to discussions of Islamic Jihad. In addition to planting exploits on the websites, the attack code was also transmitted through ad networks. The wide range of exploit carriers may explain why so many of the machines Kaspersky observed reporting to its sinkholes were domain controllers, data warehouses, website hosts, and other types of servers. Equation Group, it seems, wasn’t infecting only end user computers—it was also booby-trapping servers known to be accessed by targeted end users.

Equation Group exploits are notable for the surgical precision exercised to ensure that only an intended target was infected. One Equation Group-written PHP script that Kaspersky unearthed, for instance, checked if the MD5 hash of a website visitor’s username was either 84b8026b3f5e6dcfb29e82e0b0b0f386 or e6d290a03b70cfa5d4451da444bdea39. The plaintext corresponding to the first hash is “unregistered,” an indication that attackers didn’t want to infect visitors who weren’t logged in. The second hash has yet to be deciphered.

“We could not crack this MD5, despite using considerable power for several weeks, which makes us believe [the plaintext username] is a relatively complex one,” Raiu said. “It definitely indicates that whoever is behind this username should not be infected by the Equation Group, [and] actually it shouldn’t even see the exploit. I would assume this is either one of the group members (a fake identity), one of their partners, or a known identity of a previously infected victim.”

The PHP script also took special care not to infect IP addresses based in Jordan, Turkey, and Egypt. Kaspersky observed users visiting the site who didn’t meet any of these exceptions, yet they still weren’t attacked—an indication that an additional level of filtering spared all but the most sought-after targets who visited the site.

More recently, Kaspersky has observed malicious links on the site standardsandpraiserepurpose[.]com that looked like

standardsandpraiserepurpose[.]com/login?qq=5eaae4d[SNIP]0563&rr=1&h=cc593a6bfd8e1e26c2734173f0ef75be3527a205

where the h value (that is, the text following the “h=”) appears to be an SHA1 hash. Kaspersky has yet to crack those hashes, but company researchers suspect they’re being used to serve customized exploits to specific people. The company is recruiting help from fellow white-hat hackers in cracking them. Other hashes include:

- 0044c9bfeaac9a51e77b921e3295dcd91ce3956a

- 06cf1af1d018cf4b0b3e6cfffca3fbb8c4cd362e

- 3ef06b6fac44a2a3cbf4b8a557495f36c72c4aa6

- 5b1efb3dbf50e0460bc3d2ea74ed2bebf768f4f7

- 930d7ed2bdce9b513ebecd3a38041b709f5c2990

- e9537a36a035b08121539fd5d5dcda9fb6336423

The PHP exploit code also serves unique Web pages and HTML code to people visiting with iPhones, behavior that Kaspersky found telling.

“This indicates the exploit server is probably aware of iPhone visitors and can deliver exploits for them as well,” Kaspersky’s report published Monday explained. “Otherwise, the exploitation URL can simply be removed for these.” The report also said one sinkholed server receives visits from a large pool of China-based machines that identify themselves as Macs in the browser user agent string. While Kaspersky has yet to obtain Equation Group malware that runs on OS X, they believe it exists.

Six codenames

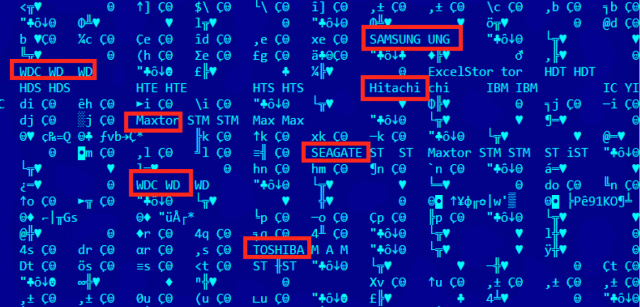

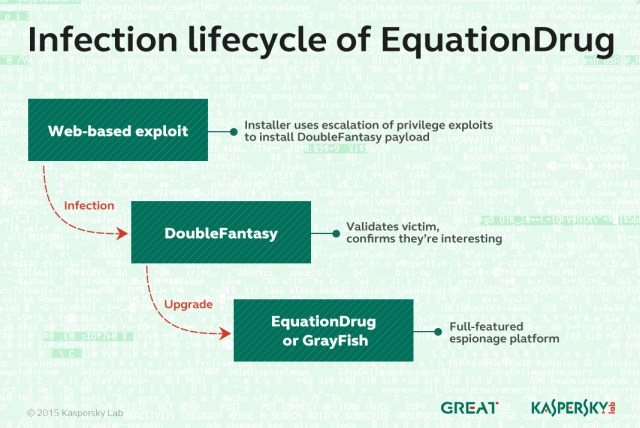

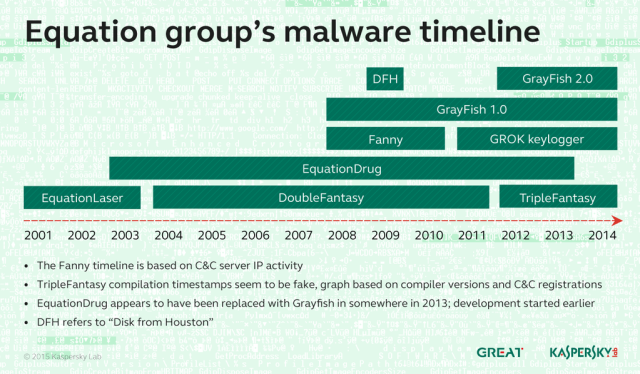

In all, Kaspersky has tied at least six distinct pieces of malware to Equation Group. They include:EquationLaser: an early implant in use from 2001 to 2004.

DoubleFantasy: a validator-style trojan designed to confirm if the infected person is an intended target. People who are confirmed get upgraded to either EquationDrug or GrayFish.

EquationDrug: also known as Equestre, this is a complex attack platform that supports 35 different modules and 18 drivers. It is one of two Equation Group malware platforms to re-flash hard drive firmware and use virtual file systems to conceal malicious files and stolen data.

It was delivered only after a target had been infected with DoubleFantasy and confirmed to be a target. It was introduced in 2002 and was phased out in 2013 in favor of the more advanced GrayFish.

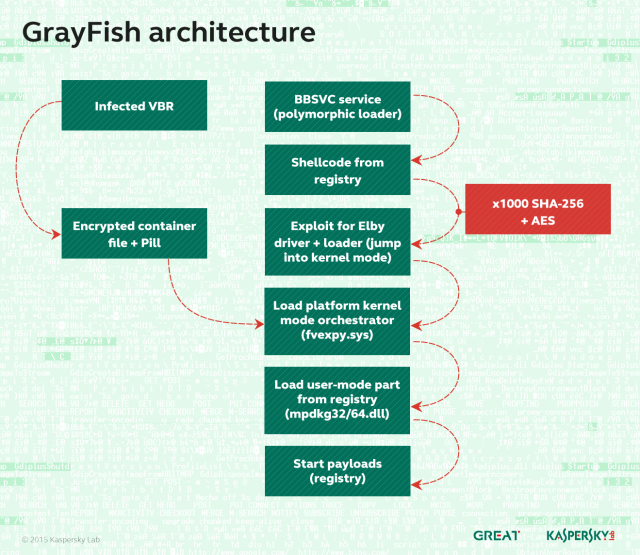

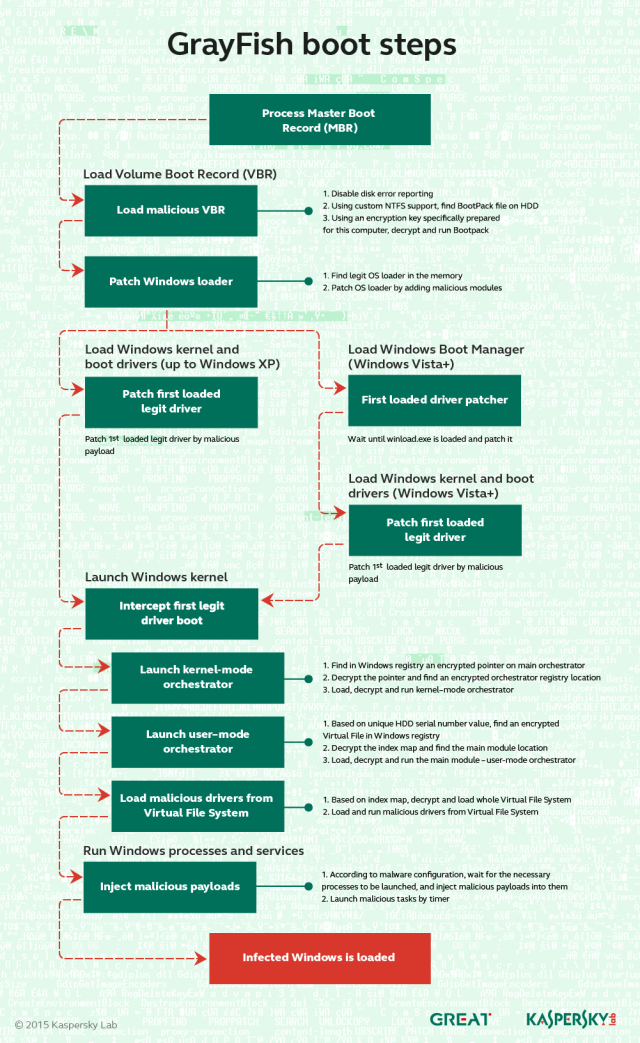

GrayFish: the successor to EquationDrug and the most sophisticated of all the Equation Group attack platforms. It resides completely in the registry and relies on a bootkit to take hold each time a computer starts. Whereas EquationDrug re-flashed hard drives for six models, GrayFish re-flashed 12 classes of hard drives. GrayFish exploits a vulnerability in the CloneCD driver ElbyCDIO.sys—and possibly drivers of other programs—to bypass Windows code-signing requirements.

GrayFish is the crowning achievement of the Equation Group. The malware platform is so complex that Kaspersky researchers still understand only a fraction of its capabilities and inner workings. Key to the sophistication of GrayFish is its bootkit, which allows it to take extraordinarily granular control of the machines it infects.

“This allows it to control the launching of Windows at each stage,” Kaspersky’s written report explained. “In fact, after infection, the computer is not run by itself anymore: it is GrayFish that runs it step by step, making the necessary changes on the fly.”

Fanny: A computer worm that exploited what in 2008 were two zero-day vulnerabilities in Windows to self-replicate each time an infected USB stick was inserted into a targeted computer. The main purpose of Fanny was to conduct reconnaissance on sensitive air-gapped networks. After infecting a computer not connected to the Internet, Fanny collected network information and saved it to a hidden area of the USB drive. If the stick was later plugged in to an Internet-computer, it would upload the data to attacker servers and download any attacker commands. If the stick was later plugged into the air-gapped machine, the downloaded commands would be executed. This process would continue each time the stick was switched between air-gapped and Internet-connected machines.

TripleFantasy: A full-featured backdoor sometimes used in tandem with GrayFish.

Mistakes were made

No matter how elite a hacking group may be, Raiu said, mistakes are inevitable. Equation Group made several errors that allowed Kaspersky researchers to glean key insights into an operation that went unreported for at least 14 years.

Kaspersky first came upon the Equation Group in March 2014, while researching the Regin software that infected Belgacom and a variety of other targets. In the process, company researchers analyzed a computer located in the Middle East and dubbed the machine “Magnet of Threats” because, in addition to Regin, it was infected by four other highly advanced pieces of malware, including Turla, Careto/Mask, ItaDuke, and Animal Farm. A never-before-seen sample of malware on the computer piqued researchers’ interest and turned out to be an EquationDrug module.

Following the discovery, Kaspersky researchers combed through their cloud-based Kaspersky Security Network of exploits and infections reported by AV users and looked for similarities and connections. In the following months, the researchers uncovered additional pieces of malware used by Equation Group as well as the domain names used to host command channels.Perhaps most costly to the attackers was their failure to renew some of the domains used by these servers. Out of the 300 or so domains used, about 20 were allowed to expire. Kaspersky quickly registered the domains and, over the past ten months, has used them to “sinkhole” the command channels, a process in which researchers monitor incoming connections from Equation Group-infected machines.

One of the most severe renewal failures involved a channel that controlled computers infected by “EquationLaser,” an early malware platform abandoned around 2003 when antivirus programs began to detect it. The underlying domain name remained active for years until one day, it didn’t; Kaspersky acquired it and EquationLaser-infected machines still report to it.

“It’s really surprising to see there are victims around the world infected with this malware from 12 years ago,” Raiu said. He continues to see about a dozen infected machines that report from countries that include Russia, Iran, China, and India.

Raiu said 90 percent or more of the command and control servers were closed last year, although some remained active as recently as last month.

“We understand just how little we know. It also makes us reflect about how many other things remain hidden or unknown.”

The sinkholes have allowed Kaspersky researchers to gather key clues about the operation, including the number of infected computers reporting to the seized command domains, the countries in which these compromised computers are likely located, and the types of operating systems they run.

Another key piece of information gleaned by Kaspersky: some machines infected by Equation Group are the “patients zero” that were used to seed the Stuxnet worm so it would travel downstream and infect Iran’s Natanz facility.

“It is quite possible that the Equation Group malware was used to deliver the Stuxnet payload,” Kaspersky researchers wrote in their report.

Other key mistakes were variable names, developer account names, and similar artifacts left in various pieces of Equation Group malware. In the same way cat burglars wear gloves to conceal their fingerprints, attackers take great care to scrub such artifacts out of their code before releasing it. But in at least 13 cases, they failed. Possibly the most telling artifact is the string “-standalonegrok_2.1.1.1” that accompanies a highly advanced keylogger tied to Equation Group.

Another potentially damaging artifact found by Kaspersky is the Windows directory path of “c:\users\rmgree5” belonging to one of the developer accounts that compiled Equation Group malware. Assuming the rmgree5 wasn’t a randomly generated account name, it may be possible to link it to a developer’s real-world identity if the handle has been used for other accounts or if it corresponds to a developer’s real-world name such as “Richard Gree” or “Robert Greenberg.”

Kaspersky researchers still don’t know what to make of the 11 remaining artifacts, but they hope fellow researchers can connect the strings to other known actors or incidents. The remaining artifacts are:

- SKYHOOKCHOW

- prkMtx – unique mutex used by the Equation Group’s exploitation library (gPrivLibh)

- “SF” – as in “SFInstall”, “SFConfig”

- “UR”, “URInstall” – “Performing UR-specific post-install…”

- “implant” – from “Timeout waiting for the “canInstallNow” event from the implant-specific EXE!”

- STEALTHFIGHTER (VTT/82055898/STEALTHFIGHTER/2008-10-16/14:59:06.229-04:00

- DRINKPARSLEY – (Manual/DRINKPARSLEY/2008-09-30/10:06:46.468-04:00)

- STRAITACID – (VTT/82053737/STRAITACID/2008-09-03/10:44:56.361-04:00)

- LUTEUSOBSTOS – (VTT/82051410/LUTEUSOBSTOS/2008-07-30/17:27:23.715-04:00)

- STRAITSHOOTER – STRAITSHOOTER30.exe

- DESERTWINTER – c:\desert~2\desert~3\objfre_w2K_x86\i386\DesertWinterDriver.pdb

Hacking without a budget

The money and time required to develop the Equation Group malware, the technological breakthroughs the operation accomplished, and the interdictions performed against targets leave little doubt that the operation was sponsored by a nation-state with nearly unlimited resources to dedicate to the project. The countries that were and weren’t targeted, the ties to Stuxnet and Flame, and the Grok artifact found inside the Equation Group keylogger strongly support the theory the NSA or a related US agency is the responsible party, but so far Kaspersky has declined to name a culprit. NSA officials didn’t respond to an e-mail seeking comment for this story.

Update: Reuters reporter Joseph Menn said the hard-drive firmware capability has been confirmed by two former government employees. He wrote:

A former NSA employee told Reuters that Kaspersky’s analysis was correct, and that people still in the intelligence agency valued these spying programs as highly as Stuxnet. Another former intelligence operative confirmed that the NSA had developed the prized technique of concealing spyware in hard drives, but said he did not know which spy efforts relied on it.

What is safe to say is that the unearthing of the Equation Group is a seminal finding in the fields of computer and national security, as important, or possibly more so, than the revelations about Stuxnet.

“The discovery of the Equation Group is significant because this omnipotent cyber espionage entity managed to stay under the radar for almost 15 years, if not more,” Raiu said. “Their incredible skills and high tech abilities, such as infecting hard drive firmware on a dozen different brands, are unique across all the actors we have seen and second to none. As we discover more and more advanced threat actors, we understand just how little we know. It also makes us reflect about how many other things remain hidden or unknown.”

via arstechnica.com