The global race is on to develop 5G, the fifth generation of mobile network. While 5G will follow in the footsteps of 4G and 3G, this time scientists are more excited. They say 5G will be different – very different.

If you’re thinking, “Great, that’s the end of my apps stalling, video faltering, and that everlasting load sign,” then you are right – but that’s only part of the story.

“5G will be a dramatic overhaul and harmonisation of the radio spectrum,” says Prof Rahim Tafazolli who is the lead at the UK’s multimillion-pound government-funded 5G Innovation Centre at the University of Surrey.

That means the opportunity for properly connected smart cities, remote surgery, driverless cars and the “internet of things”.

So, how best to understand this joined-up, superfast, all-encompassing 5G network? It seems that the term “harmonisation of the radio spectrum” is key.

A quick refresher: Data is transmitted via radio waves. Radio waves are split up into bands – or ranges – of different frequencies.

Each band is reserved for a different type of communication – such as aeronautical and maritime navigation signals, television broadcasts and mobile data. The use of these frequency bands is regulated by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU).

It is too early to say exactly what 5G products will look like

It is too early to say exactly what 5G products will look likeCurrently, the radio frequency spectrum is a bit of a mess. As new technologies have been developed, frequencies for them to use have been squeezed into its gaps.

This has caused problems with connection speeds and reliability.

So, to pave the way for 5G the ITU is comprehensively restructuring the parts of the radio network used to transmit data, while allowing pre-existing communications, including 4G and 3G, to continue functioning.

100 times faster

5G will also run faster, a lot faster.

Prof Tafazolli now believes it is possible to run a wireless data connection at an astounding 800Gbps – that’s 100 times faster than current 5G testing.

When Samsung announced in 2013 it was testing 5G at 1Gbps, journalists excitedly reported that would mean an HD film could be downloaded in a second.

A speed of 800Gbps would equate to downloading 33 HD films – in a single second.

In June 2000 Samsung released the IMT2000, touted as the world’s first web video phone

In June 2000 Samsung released the IMT2000, touted as the world’s first web video phone5G’s capacity will also have to be vast.

“The network will need to cope with a vast increase in demand for communication,” says Sara Mazur, head of Ericsson Research, one of the companies leading the development of 5G.

By 2020 it is thought that 50 billion to 100 billion devices will be connected to the internet. So, connections that run on different frequency bands will be established to cope with demand.

Raising the capacity of a network is a little like widening a road tunnel.

If you add more lanes more cars can go through. And ordering makes it more efficient: some lanes for long-distance, others lanes for local traffic.

The huge rise in connected devices will be due to a boom in inanimate objects using the 5G network – known as the internet of things.

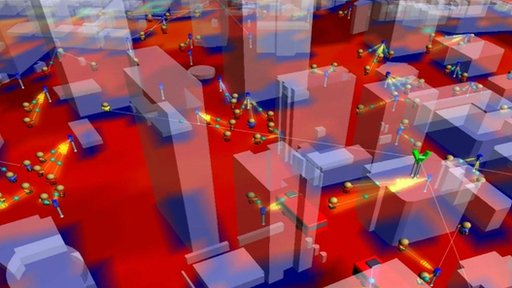

Self-driving cars talk to each other to avoid accidents

Self-driving cars talk to each other to avoid accidentsIt won’t be just products like remotely controlling your heating or that mythical fridge ordering you more milk, trains could tell you which seats are free while they are in the station.

Devices will be able to choose dynamically between which of three still-to-be-determined bandwidths they use to avoid any of frequencies from becoming overloaded, explains Prof Tafazolli.

“Only once these frequencies are set and established can product development begin,” Ms Mazur adds.

The aim is for the first of the frequency bands to come into use around the year 2020, with the other two to follow soon after.

Small masts could be used where buildings might block higher frequencies

Small masts could be used where buildings might block higher frequenciesAnother defining feature will be that, crucially, 5G shouldn’t break.

“It will have the reliability that you currently get over fibre connections,” says Sara Mazur.

Advances in antenna technology promise an end to sudden data connection drop-outs.

This will be essential for safety. Companies including China’s Huawei are already talking about using 5G to let driverless cars communicate with each other and the infrastructure they pass.

Tech such as smart transport and remote surgery, where a human remotely operates a robot to carry out complicated operations, will rely on lower latencies too.

Latency refers to the time lag between an action and a response.

Ericsson predict that 5G’s latency will be around one millisecond – unperceivable to a human and about 50 times faster than 4G.

This will be critical, for example, if doctors are to command equipment to carry out surgery on patients located in different buildings.

5G trial network

So how much will it all cost? Ericsson and Huawei say they simply don’t know yet.

Until the product development phase starts it is too early to tell.

Japan wants to play host, not just to the 2020 Olympics, but also to the world’s first commercial 5G network

Japan wants to play host, not just to the 2020 Olympics, but also to the world’s first commercial 5G networkBut that doesn’t stop them from wanting to flaunt their research to the market.

In South Korea, which spearheaded work on 4G, Samsung hopes to launch a temporary trial 5G network in time for 2018’s Winter Olympic Games.

Not to be outdone, Huawei is racing to implement a version for the 2018 World Cup in Moscow.

Despite such apparent rivalries and the huge sums each is investing in R&D, the bigger story is that they are co-operating to deliver 5G. And that in turn paves the way for potentially unmatched new technologies.

“That’s until 6G comes along in around 2040,” Prof Tafazolli remarks.

via bbc.com